I owe a lot to Michael Dellert. Not only did his Matter of Manred series inspire my own Middle Grade fiction Middler’s Pride, but he’s also kindly bought me time–I mean, offered to write a guest post while I frantically grade end-of-term projects and revise my own short story, “Normal’s Menace.” Take it away, Michael!

Lately on my own blog, I’ve been concerned with the process of rewriting. My most recent work, The Wedding of Eithne, proved to be more challenging to rewrite than any of my previous books, so in an effort to help myself understand and work through that revision, I wrote a series of articles that explore my own rewriting process.

Lately on my own blog, I’ve been concerned with the process of rewriting. My most recent work, The Wedding of Eithne, proved to be more challenging to rewrite than any of my previous books, so in an effort to help myself understand and work through that revision, I wrote a series of articles that explore my own rewriting process.

But the technical matters that fall under the umbrella of “rewriting” are vast and deep, and it’s hard to do them all justice. So I jumped at the chance to do a guest post for Jean Lee, where I could dig a little deeper into some of these matters of technique. And as a writing coach and an editor, I can tell you, one of the most important techniques to master is dialogue.

Study the Masters of Dialogue

The work of dramatists in theatre and film is entirely concerned with the realistic portrayal of believable and effective dialogue. A study of successful playwrights and their works can only improve one’s own dialogue in narrative fiction.

Recommended reading (by no means exhaustive):

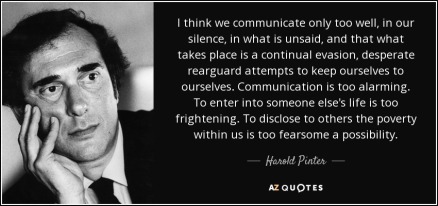

Recommended reading (by no means exhaustive):- Harold Pinter, The Birthday Party, The Room, and The Homecoming

- Arthur Miller, The Crucible and Death of a Salesman

- Howard Richardson and William Berney, Dark of the Moon

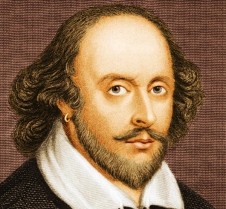

- William Shakespeare

- Sean O’Casey

We Don’t Talk Like We Write

I recently had the opportunity to edit an academic paper for my high-school-aged  daughter. She’s a good, smart kid, and she had all the information she needed to write an effective term paper. But, oh my gaaaawd, she TOTALLY writes like she tawks!

daughter. She’s a good, smart kid, and she had all the information she needed to write an effective term paper. But, oh my gaaaawd, she TOTALLY writes like she tawks!

Conversely, people don’t talk like they write. They stutter, they digress, they misuse grammar, contract words, and speak in dialect, slang, jargon, argot, idiom, cant, parlance, vernacular, patois, and parole.

Language is a living, breathing thing, and it changes every day, every minute, with every utterance of every person on Earth. Just look at the difference between Shakespeare’s English and the script of the latest Avenger’s film. Believe it or not, linguistically, both examples are considered to be “Modern English,” yet most people today can’t understand even the simplest of Shakespeare’s lines without close reading and study.

So when it comes to dialogue, take the “rule book” and throw it out the window.

Principles of Dialogue

But just because there aren’t rules doesn’t mean there aren’t some principles to consider. Consider these principles as you look over your own writing and try to bring your dialogue to life.

The surest way to kill the living essence of your characters is by insisting that they always make sense.

When you follow the labyrinth of most conversations, you discover one constant: People are always trying to get what they want. But this doesn’t mean that characters are always clear in articulating their desires, or that they are being truthful, or that they must understand each other. Conflict thrives in the space between desire, truthfulness, and misunderstanding.

The purpose of dialogue is to reflect the life and death stakes for your characters. At the core of even the most mundane exchange is a yearning for something more. By staying connected to your characters’ driving wants, their speech will reflect an attempt to achieve those desires.

Dialogue isn’t linear, nor is it logical. With each attempt, your characters are met with antagonistic forces. The tension builds through the scene as each character attempts to realize his goal.

Dialogue isn’t linear, nor is it logical. With each attempt, your characters are met with antagonistic forces. The tension builds through the scene as each character attempts to realize his goal.

If your prose feels wooden or transparent, as if you’re just trying to move the story forward, you should ask yourself, “What do these characters want?” Beneath the thin veneer of civility and the most banal conversation, life and death struggles are at work.

In rewriting your work, if a scene isn’t working, it doesn’t take long to pull out a fresh sheet of paper and write a stream-of-consciousness dialogue. Write it quickly. Surprise yourself with what the characters want to say.

It’s often in the rewrite that dialogue comes alive. You have a little more security with your structure and you can loosen the reins.

Language is a means of communicating desire. Whether it has to be seen and heard, to gain empathy, curry favor, get information, feel close, punish, win the girl, hurt, destroy, reassure, secure a position—we all speak in an attempt to get something.

But here’s the thing: we rarely come out and say what we really want, because within every scene is an antagonistic force. Your characters all have something at stake.

In real life, people rarely say what they think and feel. Why would you expect your characters to do this?

Until you get out of your own way, your characters are all going to sound like you.

Great dialogue contains tension. It understands what’s at stake, and it walks that line. Great dialogue is specific. A single line can tell a great deal about a character.

One last thing: Your characters don’t have to speak. If they don’t want anything, keep them quiet until they tell you their heart’s desire.

Michael Dellert is an award-winning writer, editor, publishing consultant, and writing coach with a publishing career spanning 18 years. His poetry and short fiction have appeared in literary journals such as The Backporch Review, The Harbinger, Idiom, and Venture. His poetry has also appeared in the anthologies The Golden Treasury of Great Poems and Dance on the Horizon, and he is a two-time winner of the Golden Poet Award from World of Poetry Press. He currently lives and works in the Greater New York City area as a freelance writer, editor, and publishing consultant. He is the author of the heroic fantasies of the Matter of Manred Saga: Hedge King in Winter, A Merchant’s Tale, The Romance of Eowain and the forthcoming book, The Wedding of Eithne. His blog, Adventures in Indie Publishing, is a resource for creative writers of all kinds.

To know something today that yesterday had never occurred to me is a fine thing. A tweet is due, young Ms Lee.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My thanks. 🙂 x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mike! I appreciate it! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Deserved.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent post Mr D. And Lady J…. love the revamp

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Shehanne! And hasn’t Jean Lee done wonders with the place? Love the redesign!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh, hush, you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

She had indeed. I love it . hope you are good Mr D xxxxxxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m very well, Shehanne, thank you! How’s Scotland getting along? Are you keeping everyone in line? 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lots of great advice. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure! I hope it’s useful to you! 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

I like your blog’s new look, Jean!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! It felt time to freshen things up a bit. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the new drapes…! 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

(snorts) Thanks. 🙂

LikeLike

Yep. Amen to this! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, I don’t think I ever got an “Amen” before. Thank you, brother! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pleasure! Though, I’d prefer to be called, ‘sister’, but agree, it probably doesn’t work as well 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

(hissed whisper) MICHAEL!

Ahem.

Hi, Skilbey! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

What? I thought we lived in a post-gender world now… 😉 Joking aside, I’m sorry, my mistake. “Amen, sister” works just as well, if not harder, and deserves to get paid just as much. I hope that qualifies for an “Amen!”as well. 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

Absolutely. No worries 🙂 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great advice from an excellent author!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh, very kind words, thank you! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

I totally agree on studying the greats like Shakespeare. I beg to differ on the part about “writing like we talk”. It’s not going to be exactly the same because let’s face it people don’t…. they don’t… like, finish their sentences when they talk, or like they get distracted and talk about something totally different… but at the same time, I think writing should reflect something of the rhythms and cadences of speech; otherwise, it sounds weird and unnatural.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You just reminded me of David Mamet. No one the way he writes in reality, but for some reason, his rhythms and cadences fit his staged universe. Perhaps because we come to expect that of him like we expect Jason Voorhees to chop up nubile teens at a campground, I suppose.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agreed that taken to an extreme, a book with dialogue that perfectly mimics our actual everyday speech would be a study in incomplete thoughts and incoherent interjections like “Uhm…”. But listening to and studying real world dialogue can help to give one’s dialogue the cadences of actual speech. As my own worst example, I often find that my characters launch off into speeches in their dialogue. In my rewriting, I realize that none of the worthy antagonists in the same scene would let them get even through the first line of that diatribe without interrupting, or that the breath lines are too long, or that the dialogue sounds wooden, because I’m writing that dialogue with a more academic bent (it’s usually some piece of important (or not so important) exposition). So that’s when I make a special effort to reimagine the dialogue as actual real-world speech: I read it out loud, I apply contractions, I interject action outside of the dialogue, I put the character’s into conflict over the dialogue, etc. This is what I mean, that it’s important to find the compromise between clarity on the page and the realistic portrayal of dialogue.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, I see what you mean. I’m very picky when it comes to dialogue, and I will put down a book in which the dialogue doesn’t sound realistic to me. There are some famous published authors that just aren’t good at it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

We’re all a work in progress. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: History Don’t Do Cameras | Jean Lee's World

Well ✒ penned👌👌👌

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ll pass the word on!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

If I ever write a book I know who I will thank.

Have to say Pinters language is magnificent. Similarly I like Beckett and Stoppard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s been a looong time since I read Beckett…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: #WriterProblems: Finding #Worldbuilding #Inspiration in #SmallTownLife | Jean Lee's World