History has always been the most important and most dangerous field of study in my eyes. As a student, I found the world of wartime propaganda utterly fascinating–how with the right words and imagery, facts and past events could be tainted, twisted, even erased from the society’s memory. As a Christian, I cannot understand why those of, say, the Amish life, live by “forgive and forget,” which has lead to a terrifyingly high rate of sexual abuse in families, since the abuser never faces any consequence for the act. He asks for forgiveness; therefore, the sin is forgiven and must be forgotten, and nothing prevents him from raping or molesting yet again. Without history, we lose our only true teacher of human nature’s scope: its heights of selflessness, its depths of wretchedness.

History is not something one often trips upon by accident. There is but the single weed budding from roots that run deep and far, or the curved stone in the dirt which, as one digs, and brushes, and digs, becomes a bone. History hides itself in the present mess, and hides well, just as any good mystery should.

Ellis Peters, aka Edith Pargeter, knew this all too well as she wrote The Cadfael Chronicles. Her stories of this Rare Benedictine are set in the 12th century during a civil war between two monarchs vying for England’s throne. The time’s rife with secret messages, castle sieges, hidden treasures, betrayals and all sorts of other delicious things that make the period rich with living…and killing, but also living.

Some years have passed since I’d read a Cadfael, and I decided to rectify that when we traveled to the North Woods (the way up north where the bald eagles hang out in ditches and bears will meander down your driveway and turtle nests are smashed by an old Polish woman with a shovel). I can read in the car; Bo cannot, so he prefers to drive. (That, and I apparently drive a bit too crazy for his liking. Wuss.) This title was not adapted for the Mystery! series starring thespian treasure Sir Derek Jacobi, which meant the mystery would be new to me. Yay!

The Hermit of Eyton Forest begins with, of course, death, but this one’s natural: a father dies of his battle injuries, orphaning his son who was already in the abbey’s care. When the abbey refuses to send him home with his scheming grandmother, who has a marriage in the works for this ten-year-old, the grandmother takes in “a reverend pilgrim” and his young assistant to live in the hermitage on her land between the abbey and the boy’s inherited manor (33). The detail quickly fades in a passage of time, and it sounds like this pilgrim Cuthred has changed the grandmother’s mind about suing the abbey for custody.

Act I winds down with a conversation between friends: Cadfael and the Sheriff of Shrewsbury. War-talk is very common in these books, especially since Shrewsbury isn’t far from the Welsh border, where many fugitives run. So when Chapter 4 meandered through a conversation about King Stephen holding Empress Maud under siege in Oxford, my eyes, erm, well, dazed over somewhat.

“There’s a tale he tells of a horse found straying not far from [Oxford], in the woods close to the road to Wallingford. Some time ago, this was, about the time all roads of Oxford were closed, and the town on fire. A horse dragging a blood-stained saddle, and saddlebags slit open and emptied. A groom who’d slipped out of the town before the ring closed recognised horse and harness as belonging to one Renaud Bourchier, a knight in the empress’s service, and close in her confidence too. My man says it’s known she sent him out of the garrison to try and break through the king’s lines and carry a message to Wallingford for her.”

Cadfael ceased to ply the hoe he was drawing leisurely between his herb beds, and turned his whole attention upon his friend. “To Brian FitzCount, you mean?” (53)

Blah blah, war things, blah blah. Get to the murder already!

But Peters is no fool. If she’s spending a little time on “war stuff,” it’s for a reason. On the one hand, this gives us a taste of how monarchs struggle to reach out for help in the midst of a siege. It’s an historically accurate strategy, and a fine moment on which to focus for a sharper taste of medieval warfare vs the typical “argh” and swords banging and catapults and the like we always see in movies. On the other hand, this past event is a clue to solve the murders: a nobleman hunting a runaway villein is found stabbed in the back, and the hermit Cuthred is also found dead. Peters buried the clue in that conversation of war, that which we readers would think is just material for the period, not for the plot.

Yet it all comes very much to the forefront in Act III. The nobleman’s son, for instance, sets the reveal into motion when he sees the pilgrim’s body:

“But I know this man! No, that’s to say too much, for he never said his name. But I’ve seen him and talked with him. A hermit–he? I never saw sign of it then! He wore his hair trimmed in Norman fashion…And he wore sword and dagger into the bargain,” said Aymer positively, “and as if he was well accustomed to the use of them, too….It was only one night’s lodging, but I diced with him for dinner, and watched my father play a game of chess with him.” (202)

It’s not like the medieval period had finger prints on database or, you know, pictures for comparison. Identity hinged on being known, and in that kind of war-torn world, you never know who’s going to know you. In this case, Aymer, son of the dead nobleman, unwittingly revealed this holy man to be a fraud, therefore ruining the grandmother’s schemes to have the holy hermit force her grandson to marry a neighbor’s daughter for more land. The nobleman had gone to the hermit, thinking his assistant might be the runaway villein he’s hunting–and here he sees the soldier he had played games with posing as a pilgrim.

So, who is this hermit that killed to keep his true identity dead in history, and who killed him? Not the nobleman, being already dead and all. And not the nobleman’s son.

Well, there is a falconer who has been loitering about the abbey, and who uses Empress Maud’s coins for alms. Cadfael, being a soldier in the Crusades before coming to the cloister, has his own opinions about divine duties in warfare, and chooses to say nothing rather than speak with the abbot, who is publicly aligned with King Stephen: “My besetting sin…is curiosity. But I am not loose-mouthed. Nor do I hold any honest man’s allegiance against him” (143). Turns out this falconer is on a hunt for none other than the man who had taken off with the treasure and war correspondence from the bloody saddlebags discussed on page 53, and this thief was none other than the fake hermit Cuthred:

“He had killed Cuthred. In fair fight. He laid his sword by, because Cuthred had none. Dagger against dagger he fought and killed him…for good reason,” said Cadfael. “You’ll not have forgotten the tale we heard of the empress’s messenger sent out of Oxford, just as King Stephen shut his iron ring round the castle. Sent forth with money and jewels and a letter for Brian FitzCount, cut off from her in the woods along the road, with blood-stained harness and empty saddlebags. The body they never found.” (219)

Had Peters simply dumped this information on us at the end–as Agatha Christie has done a few times with Poirot–I would have been pissed. But Peters didn’t; she took advantage of Act I’s slow build and shared the clue inside her war stories. Readers may not remember this tale by story’s end, but Peters doesn’t cheat them with an absurd reveal thrown in at the end, either. She shares only the history that matters; it’s the reader’s responsibility to remember it.

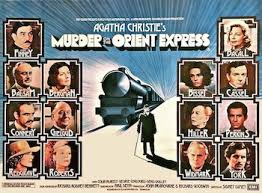

On the flip-side of this, when someone hacks up a mystery by throwing history at us too early, I get rather miffed. Murder on the Orient Express is guilty of just such a crime.

No, no, not the book. There’s a reason so many look to this particular Poirot title as one of Christie’s masterworks. The first Act establishes Poirot on his way home from a case on the continent; this is why he eventually boards the Orient Express with other passengers. The body’s discovered in Chapter 5, and it’s in Chapter 7 we get the history-reveal:

The doctor watched [Poirot] with great interest. He flattened out the two humps of wire, and with great care wriggled the charred scrap of paper on to one of them. He clapped the other on top of it and then, holding both pieces together with the tongs, held the whole thing over the flame of the spirit lamp….It was a very tiny scrap. Only three words and a part of another showed.

-member little Daisy Armstrong. (161)

This clue both slows and tightens the pace: Poirot and his comrade recall this kidnapping and murder of the child Daisy a few years ago. It turns out the murder victim at their feet was that same kidnapper. From here the identities of the other passengers are worked out as well as their connections to the Armstrong child.

No, the book is not the guilty party. That verdict belongs to the 1974 film.

It begins with a newspaper/newsreel montage about the kidnapping and murder of child Daisy Armstrong. It lasts a minute, and that’s a minute too long.

It then jumps to five years later, and the gathering of characters to the train.

For one who’s unfamiliar with the book, this jump from dead child to Istanbul has got to be really confusing. For those who read the book–like me–this little montage kills the mystery. What does that footage do? Well, it shows readers that there’s a revenge in the works. We already want justice for that little girl, so whoever gets killed on the train deserves it before it even happens, which means readers won’t dare to connect with any of those other characters because they know one of them’s a wretch who needs justice bled out of him. In the book, we know nothing incriminating about any of the characters in Act I. In Act II, we’re still getting over the shock of a murder happening in an isolated, snow-bound train, where we know the murderer must still be hiding among innocent lives who sure need protection, and then, then, we find out the victim was a child murderer. It’s a double-whammy of a reveal thanks to present and past smashing together.

But when readers learn the history first, they know what to expect in the present. This is a must for so many aspects of life and story alike, but in mysteries? Part of what makes a mystery a mystery is not knowing what to expect.

PS: I dare to get excited about the upcoming Branagh version of the story despite Branagh’s mustache. Your thoughts?