“Since I was surrounded by poisons, perhaps it was natural that death by poisoning should be the method I selected.” –Agatha Christie

Welcome back, my fellow creatives!

I have written about the great Dame of Mystery for a long time here–about ten years, in fact. (YOWZA.) While I never felt up to the task of writing a mystery myself, I loved watching the likes of Hercule Poirot put his little grey cells to use and methodically dissect every crime and criminal he encountered. Over the past few years I FINALLY decided to give Miss Marple a try, and while a couple novels irked me (I’m looking at you, Moving Finger), I did find great joy in other stories, particularly the short fiction.

One of the great powers behind the Christie stories is the expertise of Christie herself: a hospital dispenser for both world wars and a professional chemist, Christie understood the dangerous power of all the little bottles of powders and fluids she’d give patients day after day. Her knowledge of how these substances could poison a body–no, not just that they could, but how they could–meant she could drop little clues in a novel or fiction that would allude to the poisonous murder weapon.

Not surprisingly, Christie provided her murderers with poison more than any other murder weapon. She filled notebooks with important points about various poisons, even bits of brainstorming about how the effect of a poison may change depending on how it’s taken, such as in cake frosting (that story never came to fruition, sadly). (Curran, 2011; Harkup, 2015).

So let us have a little garden party, you and I. We can sit back and admire Miss Marple’s roses while she knits, and we shall sip our tea and enjoy some scones with clotted cream and jam while Miss Marple sweetly speaks of murder.

The Story: “The Tuesday Night Club”

The Poison: Arsenic

Miss Marple’s Favorite Clue: “Cooks nearly always put hundreds and thousands on trifle, dear,” she said. “Those little pink and white sugar things. Of course when I heard they had had trifle for supper and that the husband had been writing to someone about hundreds and thousands, I naturally connected the two things together. That is where the arsenic was–in the hundreds and thousands.”

Arsenic has a peculiar history. It’s actually quite a common element, one the Greeks and Egyptians knew well enough could kill. The Italian and French Renaissance courts saw arsenic deployed often to deal with unwanted royalty. When the Industrial Revolution came along, and arsenic deposits could be scraped out of chimneys after purifying the iron and lead extracted from the earth, access to the poison changed. As Kathryn Harkup, author of A is for Arsenic: The Poisons of Agatha Christie put it: “Prices plummeted, and soon anyone and everyone could afford enough arsenic to dispatch an unwanted relative or inconvenient enemy” (p.23).

Now, how does arsenic find its way into food? Sure, it was in skincare products and clothing dye and wallpaper and pesticides, but food? Well, if the arsenic is kept as a white powder, it can look just like flour or powdered sugar. In fact, one sweetmaker in 1858 used some arsenic by accident while preparing a batch of sweets, leading to over 200 people falling gravely ill and 20 people dying (Harkup, 2015). Arsenic needn’t be immediate, however. In small doses, one will know the likes of severe stomach issues, hair loss, skin problems, and numbness. Since these symptoms can be the result of so many other things, a slow poisoning can be easy to hide (Stevens & Klarner, 1990).

Arsenic could also look like little grains, almost like rice–which fits with Miss Marple’s epiphany regarding the hundreds and thousands. As an American, I had no idea about this “hundreds and thousands” thing until Miss Marple described what they look like. Since the other members in Marple’s gathering weren’t cooks, they hadn’t thought of such a term either, their minds all immediately considering “hundreds and thousands” to refer to money. That’s what I thought, too! Here in the States, those are called sprinkles (because that’s what you do with them (obviously)).

How easy it is to substitute the innocent for the dangerous.

~*~

The Story: “The Thumb Mark of St. Peter”

The Poison: Atropine

Miss Marple’s Favorite Clue: “The hand of God is everywhere. The first thing I saw were the black spots [on the haddock]–the marks of St. Peter’s thumb. That is the legend, you know. St. Peter’s thumb. And that brought things home to me. I needed faith, the ever-true faith of St. Peter. I connected the two things together, faith–and fish.”

Atropine is a nasty bugger. It’s very hard to detect postmortem because it breaks down so easily. Unless you know what you’re looking for, chances are you won’t find a trace of this poison, connected most often with a plant like belladonna. However, this vegetable alkaloid was also used for medicinal purposes, particularly in things like eyedrops. So, if one had a vial of this atropine to treat one’s eyes, one had plenty of poison to bump someone off. It was just a matter of getting the person to swallow it all at once so the bitter taste is only noticed too late…which, as it happens, was the case in this short story (Harkup, 2015). Miss Marple’s niece was being buried alive by rumors in her village that she had poisoned her husband, which of course wouldn’t do. Miss Marple set about to clear her niece by speaking with various folks in town, like the doctor, the husband’s father, and the house staff. She soon learned something strange was said by the husband as he died: something about a pile of fish.

Because Miss Marple’s expertise stems from studying human nature, she figured out the maids were using words they knew while trying to describe the dying man’s final word. While studying a medicinal dictionary, Miss Marple struck upon it: pilocarpine. Not unlike “Pile of carp,” wouldn’t you say? The husband had been trying to tell the staff what he needed to live, for pilocarpine and atropine can work as antidotes to each other (Harkup, 2015). The struggle with speech makes sense, as the first signs of atropine poisoning affect the mouth and throat (Stevens & Klarner, 1990).

And this little moment shows two great things about Christie and Miss Marple both. Christie knew her poisons and their antidotes, so she could work out how an uncommon medicinal thing could sound, to a layman’s ear, like something else. And Miss Marple showed her understanding of human nature by knowing people make assumptions about what they think they hear. In the end, it was the husband’s father who had poisoned his own son with his eyedrops, and wasn’t the least bit sorry about it.

How easy it is to use something useful in such a deadly way.

~*~

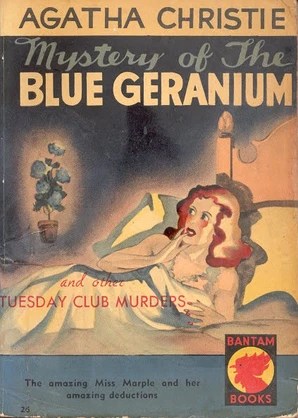

The Story: “The Blue Geranium”

The Poison: Cyanide

Miss Marple’s Favorite Clue: “I know,” said Miss Marple apologetically, “that I’ve got wasps on the brain. Poor things, destroyed in their thousands–and usually on such a beautiful summer’s day. But I remember thinking, when I saw the gardener shaking up the cyanide of potassium in a bottle with water, how like smelling salts it looked. And if it were put in a smelling-salt bottle and substituted for the real one–well, the poor lady was in the habit of using her smelling salts.”

Ah, cyanide. This little beauty shows up in over a dozen Christie mysteries via injection, drink, smelling salts, and even a cigarette (Harkup, 2015). Growing up I learned from shows like Law & Order that cyanide often smells like almonds, but Harkup schooled me in that many plants contain cyanide compounds, such as apple pips. However, bitter almonds and apricot kernels have a stronger concentration. Hence, the common smell we hear about today (2015).

This mystery features a hospital nurse with a vicious streak for her neurotic patient, an elderly woman obsessed with psychics and her smelling salts. The nurse disguised herself as a fortune-teller, warning the old woman that certain blue flowers would appear before the patient’s death. Sure enough, some of the flowers in the old woman’s room began turning blue, and soon the old woman died–not of cosmic reasons, but of cyanide in the smelling salt bottle.

In order to deceive a victim and look like smelling salts, the cyanide would likely be a compound matched with potassium or sodium. These two cyanide compounds were often used as insecticides at the time, so once again, the poison would be readily available to anyone who wanted it. Plus, because cyanide attacks a person at the cellular level, death will occur in minutes whether it’s inhaled, swallowed, or even absorbed through the skin (Stevens & Klarner, 1990). Even if someone wanted to help a person poisoned by cyanide, one couldn’t do anything without risking their own life. If someone tried to perform mouth-to-mouth, they would inhale the compound and be poisoned, too (Harkup, 2015).

How easy it is to kill with the poison that keeps on poisoning.

~*~

The Story: “The Herb of Death”

The Poison: Foxglove

Miss Marple’s Favorite Clue: “Those digitalin leaves were deliberately mixed with the sage, knowing what the result would be. Since we exonerate the cook–we do exonerate the cook–don’t we?–the question arises: Who picked the leaves and delivered them to the kitchen?”

In its early life, foxglove (the digitalis plant) can easily look like sage or spinach. Once it flowers, though, all bets are off, and folks will know they are not picking sage. Foxgloves have been used to treat the heart for centuries because digitalin alters how the heart contracts; for some patients, that kind of dosage can help, but in healthy people such an irritation to the heart can be dangerous. (Harkup, 2015; Stevens & Klarner, 1990). However, you need to take a very concentrated amount for it to kill you, which is what confuses Miss Marple and her party as one describes a dinner where everyone got sick because of the foxglove leaves, but only one died.

Christie knew that important medical tidbit regarding the potency of the chemical within the plant: sure, some would be dangerous, but it wasn’t a guaranteed way to bump someone off–especially if YOU are eating that same dinner! But as Miss Marple points out, the elderly gentleman heading that dinner had access to his own digitalin: his heart medicine. And it wouldn’t take much at all to administer the fatal dose to someone while everyone’s queasy in their rooms with a much lower dosage of the poison.

How easy it is to disguise one poisoning with another.

~*~

Well, I hope I didn’t put you off your tea. I promise you that it is proper sugar by the cream, and these sprinkles are merely a little extra something for your biscuits if you wish. Care for a scone? That’s sage in there, I’m sure. Mostly.

Coming up, I’ve got a lovely interview, another podcast, and Brian Blessed in feathers. Weeeee!

Read on, share on, and write on, my friends!

References I used, in case you are so inclined to check them out:

Stevens, S. D. & Klarner, A. (1990). Deadly Doses: A Writer’s Guide to Poisons. Writer’s Digest Books.

Harkup, K. (2015). A is For Arsenic: The Poisons of Agatha Christie. Bloomsbury.

Curran, J. (2011). Agatha Christie: Murder in the Making. Harper Collins.

Christie, A. (1985). Miss Marple: The Complete Short Stories. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.Curran, J. (2011). Agatha Christie: Murder in the Making. Harper Collins.

I recall Christie’s favorite review of her debut novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles was from a scientific journal that praised her accurate description of strychnine poisoning.

If you ever would like to watch a good mini docuseries on Christie, I highly recommended the one hosted by Lucy Worsley (she did a good one on Arthur Conan Doyle too).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooooh, thanks for the recommendation!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. Pretty much anything hosted by Lucy Worsley is guaranteed to be good. In addition to Christie and Doyle, she did a documentary on Jane Austen (available on YouTube).

LikeLike

My wife is a diamond when it comes to Miss Marple. I shall have to tell her this. Regards, Mike

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks! Hope you and yours are well. xxxxxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved Miss Marple’s movies when I was younger. Margaret Rutherford (spelling?) was superb.

LikeLike

These are the mysteries that stick with us! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Have you been hearing about the court case going on in Australia. It could be called Death by Beef Wellington.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t! Sounds like it’s worth a look. xxxxxx

LikeLike

Fabulous poisons from Agatha Christie (AKA Miss Marple) – great stuff! Also that little clip with the wonderful Brian Blessed. Excellent!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Isn’t Brian Blessed a treat? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always wondered if mystery writers weren’t writing novels, would they be real life villains? Anyhow, great post on Miss Marple and her poisons!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks! I do think Christie would have been quite a dastardly poisoner if her nature had been so inclined…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi thanks for liking my post 📫 have a great day 😀

LikeLike

I remember an old English school teacher telling the class that the brilliance of Agatha is that every tale is not like a piece of made up story telling, but it’s like recounting something that really happened, like a confession. Love that movie, so much fun. Brian is so wonderfully over the top in that one. xxxxxxx

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! Goodness, he is a right nutter in that movie…and I love it!

LikeLike

Terrific essay, Jean. Pick your poison!

LikeLike

Many thanks, my friend! I’ve been rewatching the Joan Hickson Marple specials, too. Such a delight from the 80s! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person