As a child, I spent most of my time with cozy mystery writers like Agatha Christie, P.D. James, Colin Dexter, Ellis Peters, and, of course, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. By saturating myself with mysteries, I grew accustomed to quick character development, red herrings, plot twists, and, of course, explanations. A good mystery must show the whodunnit, howdunnit, and whydunnit. If the mystery isn’t solved, then the protagonist is clearly not worth his weight in pages.

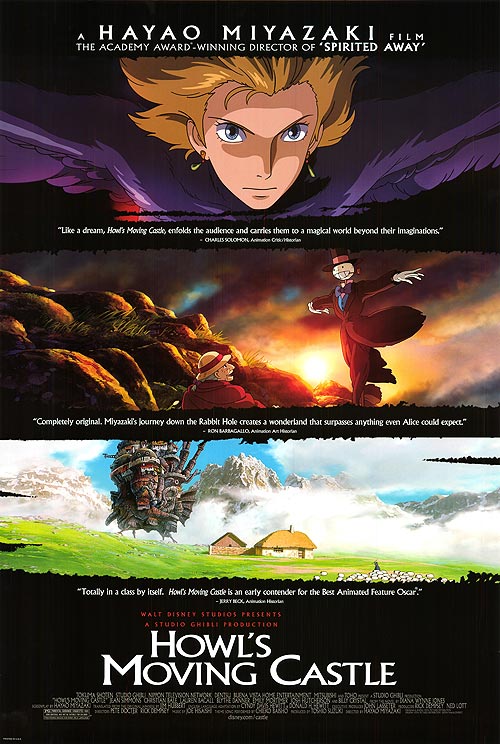

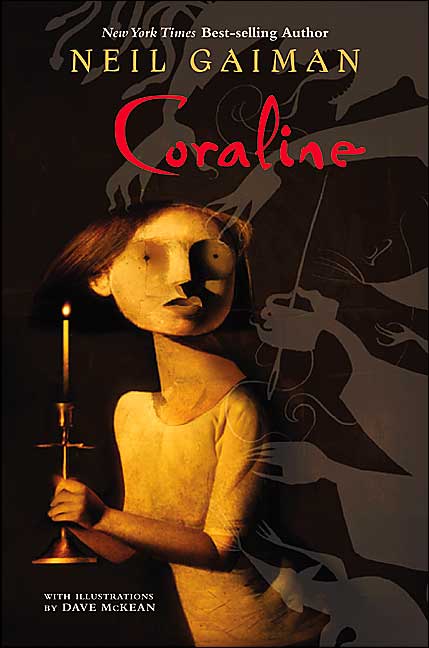

It’s with this mindset, cemented over, oh, a couple of decades, that I entered the fantasy worlds of writers like Diana Wynne Jones and Neil Gaiman via film adaptations of their stories.

While both films take great liberties with the stories, I saw enough to get hooked on these writers for life.

Now I’ve got to admit something shameful: The first time I read Coraline–before motherhood and writing were serious endeavors–I was deeply disappointed. All these kudos on the back cover about how awesome the story is, it’s the new Alice in Wonderland, blah blah blah. Gaiman doesn’t EXPLAIN anything! What IS this button-woman? Why rats? Did no one else ever notice that giant door? Surely other people lived in the flat before that. Humbug, I say!

Five years later, I hope I can say that hearts change, and that what I felt about the book before: that was a humbug, as George C. Scott’s Ebenezer Scrooge put it.

Does this mean I discovered the answers to those questions? Nope.

It means I’m okay with there being questions unanswered.

Current culture revels in creating backstory questions the initial stories were not asking:

What made Michael Myers so evil? See the movie!

When did Anakin Skywalker turn to the Dark Side of the Force? Answers revealed!

How did Hannibal become Hannibal the Cannibal? Find out now!

Why do magic ladies go bad? Disney’s got the goods on The Wicked Witch of the West and Maleficent!

Everything has to be explained. Everything has to be known.

Part of what makes fantasy fiction so enjoyable is its unknown, the extant of not-like-reality it contains. Neither the film nor book of Coraline explain what’s with the door between worlds, why there’s only one key, why sewing buttons into a child’s eyes keeps him/her in the other world, or even what the Other Mother is.

Because guess what–a kid don’t care. Coraline knows the Other Mother has her parents. She knows the Other Mother uses buttons to trap kids. She knows the Other Mother wants that key.

When I studied point of view, I realized just how vital that ignorance/acceptance trait is with a child character. While the writer knows how the world works, he can’t imbue that knowledge into the child. The child takes in the world as it enters her immediate perception, and she absorbs what impacts her personally. Coraline initially enjoys the Other Mother’s world very much, but when she’s asked to give up her eyes for buttons, she prefers her own home. Only then does the predatory nature of the Other Mother’s world become clear.

Mysteries thrive on what’s hidden: a character’s past, a buried piece of setting, and so on. But what’s hidden must also be exposed in order for a mystery to fulfill its promise to readers. Even mysteries for children will do this, as I’m currently learning from Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit for the gazillionth time, as it’s my kids’ favorite movie.

Coraline, however, is not a mystery as far as the genre’s concerned. It is a perilous adventure through a dark fantasy land, something which kids are not often exposed to. The world both excites and tests the protagonist, and because the protagonist is as young as the readers, the readers share in the experience.

As Reality often proves, there just simply isn’t an explanation for everything that occurs in our lives. We have to learn how to accept the unknown as it comes as well as how to overcome it. These require courage, strength, determination, and wit–all traits Coraline uses to survive the Other Mother’s world.

No explanation required.