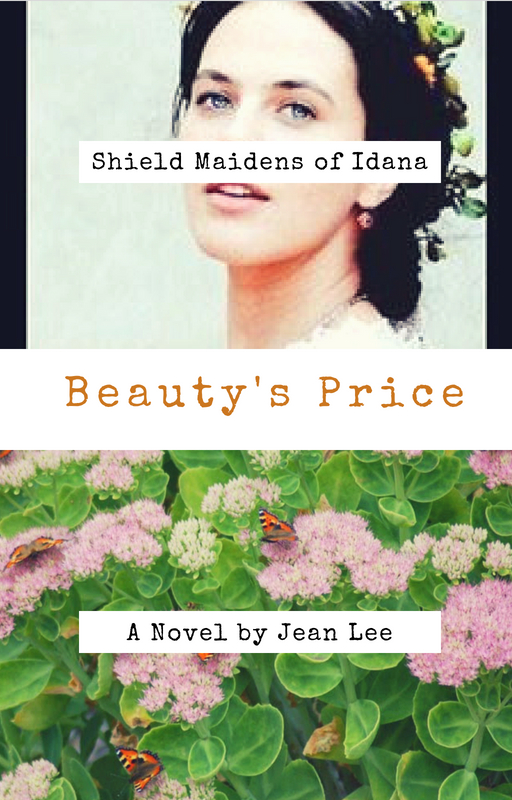

Good morning, lovely readers! What follows is a continuation of my previous three installments of free fiction–a dialogue between me and Wynne, a character from my Shield Maidens of Idana fantasy series.Today we walk with Wynne as she evades Prydwen, The Man of the Golden Hound Crest, and learn that maybe, just maybe, there is hope for her love, the smithy’s son Morthwyl.

Is that when you decided to join the Shield Maidens?

The Shield Maidens? Oh, Galene, if I had thought of them sooner… yet I was not of age, and the King’s Stronghold seemed to only make use of men, at least in Cairbail. But King’s presence or not, Trade is Law, be it done with the crown’s blessing, or not.

For the next three years, life in Cairbail flowed with the Gasirad: it sparkled with life, it stunk with decay. It all depended on where you stood: more traders came up the river and King’s Road, more business done. Father was elated, of course, which put Mother into her happy hysterics. But for whatever these traders brought into Cairbail, very little was left. And very few held to the King’s Road long after. Some of Caddock’s men were on the road one dawn as they veered off onto the small rutted road towards Morthwyl’s village. What use do farmers have for weapons and powders?

I, too, saw them from the oak where Morthwyl and I often hid. The ground had stopped feeling safe the moment Prydwen rode into our world. In the heat of summer, with the leaves at their proudest size and the bees endless in their own sweet industry near us, we felt safe.

Oh, those were the happiest hours! Morthwyl leaned against the trunk, and I against he, my head upon his shoulder, his scent filling the very air I breathed. Our fingers entwined, we would say nothing at all, our lips dancing as our feet yearned to do along Gasirad’s shores.

It was such a moment when we heard the whining of old wagon wheels, crude humor, the splash of wine, and the countless yips and cries of dogs. We dared not move the branches for a look, as the oak grew close to the road. But we could hear as they approach, hear the words, “What in blazing Hifrea a lone man’s needin’ so many bloody dogs is a mystery, make no mistake.”

“Shut yer gob, the money’s good.”

“Aye, the money, but what’s one lone man doing, asking a professional breeder such as myself, to bring not just one breed, but FIVE? And FIVE of each breed? It’s off the nut queer, it is. And ruins my offerings to many good clients for summer hunting.”

“Yer getting paid twice what any nobleman can give you. Now shut it, we don’t stay on the road long. There’s a marker somewhere round heres.”

Their noise only just started to fade when Morthwyl whispered to me, “That’s the fifth wagon I’ve heard talk like that.”

“With dogs?”

“No, but always five of something: knives, pottery, glass, furs, chairs. Have you ever heard of such a thing?”

My heart lurched as we clung to one another, for we both thought the same: my sisters and I. The five of us, a collection.

That afternoon I accompanied Tarren from Little Innean back to Cairbail with my pretense: some repaired girdles for Heledd, Ysball, and myself. I refused to wear the new ones Prydwen had bought for the five of us, all “fine leather” and “stitching done with a fairy’s hand.” Fairy, my eye. The girdles all portrayed golden hounds, and those girdles were nothing more than brands to mark us for his own. Poor Congol! He sobbed on the open street when he saw his chances with Isolda really were over.

While Tarren and I were not quite friends, our similar ages allowed for easy conversation on our journey. When we approached the last hill before Cairbail, I turned to give the forest a smile farewell, and froze.

“Did you forget something?” Tarren asked me as she searched for what I saw.

Upon a speckled grey steed sat one of those guards, the grey ones heavy with death about their hands and faces, staring at us.

“Those men of that merchant’s give me the frights,” Tarren said, shuddering. “They look like rocks dressed in clothes.”

I nodded, and wondered how much truth lay in those words.

“Isn’t that merchant fellow courting all of your sisters, and even you?”

And would you know…this was a strange sensation, but once I did it, I knew what I had done: I sneered. My heart kicked my chest. All I wanted was on the other side of that….thing. That thing, and that man, IF you can call him that, which he represented. That man who dared show up, insist he know my family, lay claim to us as if we’re some sort of lost property, and then, then, stand aghast when he hears a girl is not to be won over by money or status. The impudence! The garishness! The audacity! It all churned and bubbled into a terrific bile in my mouth, and I spat it all out, far louder than was polite to Tarren, but I didn’t care, I wanted it out: “He can have the pick of my sisters or all of them, but not me. Never me.”

Weren’t other people thrown off by how he wanted to marry all five of you? You were what, fifteen by then? That’s still more kid then woman, for goodness’ sake.

Goodness had nothing to do with it. Marriage is a business more than anything else in Idana: one marries, and money is exchanged. One marries, and money awaits for your offspring. One strives to marry above station, but not too above, that’s just as scandalous and unseemly. And while polygamy didn’t happen often outside of the aristocracy, it still happened.

Tarren thought it a bit odd, to be sure, especially when it seemed far easier to simply take me on as some sort of handmaiden. “Surely five dowries amounts to a king’s ransom. I can’t imagine how your parents or that merchant are affording all this.” I liked how Tarren always referred to Prydwen as “that merchant.” Many in Cairbail did, too, because he so very rarely showed his face. Lord Murdach has even given Father a bit of grief for sending his daughters off rather than make more sensible marriages within Cairbail. But once my sisters knew they wouldn’t have to smell the tannery all their lives, why should they bother with the likes of our townspeople?

Of course Sage Forga insisted he knew the truth. He insisted yet again as Tarren and I came to Market Street. “A new river will flow in Galene, Mistress Wynne, mark my words,” he called from his window box of herbs. The apple of his throat jumped with nervous delight. “Yes indeed, told Lord Murdach just this morn of my latest vision.” Tarren rolled her eyes as she went on towards Aedh for leather scraps. I, being the object spoken to, could not roll my eyes, let alone step away. Oh gods, send a storm upon us to close those shutters and his mouth! “I see…” His eyelids fluttered, and his hands spread before his cheeks. He rather had the look of a fish when he envisioned past visions. “I see a river of gold flowing in a crimson sunset. I see your suitor, an enchanted prince from a far-off land, who wants to love all. A new age comes for Cairbail, for aaaaall the land that is,” his hands whirled closed, “Idana.”

I considered his popping eyes, brown teeth, and sweaty face, and thought him to spend far, far too much time in the smoke of his pipe weed. “Time will reveal all, Master Forga,” I said with as much civility as could be mustered. “Good day.” I curtsied and turned to leave.

Prydwen stood but a few feet away. Where in all blessed Idana did he come from? Yet there he stood, flesh, velvet, and all, one leg bent as he flourished one side of his cloak to bow from the waist down. “My lady. Summer blesses your spirit once again. The air of wildflower and honey suits you.”

Surely, surely he spoke as he did because he knew. He knew of the tree. He knew I continued to see my Morthwyl despite my family’s schemes. Yes, I could see it in his chest, barely moving beneath that golden hound, eyes warm and bright like candles: small flames, but even the smallest flames can burn far and deep.

“I’ve come to inquire after your mother’s health, as I cannot help but do. A meager excuse to see you and your sisters, but,” he held his orange jeweled hand open to me, “I simply cannot help myself.”

He stood without steed, servant, or guard. He carried no money, no goods. Perhaps he needed none, for what he carried was deadliest of all: knowledge.

I swallowed my fear, and all my words. Of what could I accuse him? All would say he was merely protecting one of his…brides. Oh, disgusting word! To spit upon his face and run!

“Master Prydwen, what a most marvelous surprise!” Never had I been more thankful for Sage Forga than in that moment, especially when he burst from his door in a strange mix of sliding on a horse pat and bowing at the waist while still trying to draw smoke from his pipe. “I simply must speak with you soon. Such omens fly above me and crawl beneath my feet that point to you, and only you, Noble Sire!”

“Let me not detain you from a conference of such importance, Master Forga.” I curtsied to him and walked around Prydwen without so much as a goodbye. Enough of his gem-stoned wooing and endless compliments. Enough of his golden hounds and gifts. I cared not that I left his hand shaking in the air. Sage Forga is not easily deterred, especially when he is full of visions that require a bit of gold to complete.

I nearly collided with Aedh’s precious mule as I moved with all civil haste to Caddock’s warehouse. Even at 15, I still met Caddock for my lessons. Though Mother thought my skills proficient, Father noted Caddock also a fine teacher in the ways of goods keeping. She’ll be such a help to Prydwen that way, my dear wife.

Ugh. Oh ugh, these are the moments I nearly lose myself…a moment while my stomach calms….please, sit with me here, Adyna’s neighbor Niall always has some ol and wine on hand. Some cheese dipped in batter sounds wonderful, thank you.

Sounds like Sage Forga knows how to butter up the money. I’m guessing that Lord Murdach, being the guy in charge of a town, didn’t like being showed up by some outsider.

You use words strangely, but…if I understand you, yes. As performers need to share the stage without dominating one another, so Cairbail felt a stage, and Prydwen an actor who had walked through the audience and onto the boards without permission. “What’s a man like that doing here?” I heard Lord Murdach say as a dagger whistled and thunk a far box of what I hoped to be fruits, beans, anything not alive. “Don’t get me wrong, Caddock, I enjoy an upturn in business as much as any man—”

“But the upturn came a bit quick.” Caddock’s voice was low, clear, and disquieting.

“Precisely. A little black market makes no mind, but he has gods-know-how-many barges and wagons coming up from the ocean filled with gods-know-what because he’s duped the inspectors into thinking it’s all just typical animal feed and livestock. You tell me who needs five oxen and doesn’t farm!” The next dagger struck but a few feet in front of my nose as I stood, still out of site in this labyrinth of crates and sacks. “He’s got something going on, but everyone’s too keen for his coin to care. It’s only my title, my seat, my life on the line with his business.”

“I fully share in your skepticism, Sir.”

“Good. And good on you for not storing his goings-on here. He’s got boxes of all sorts tucked into every other warehouse in town. Don’t like it. Not one bit.”

“Thank you, Sir.”

I came into view, then, halting their dialogue. Caddock’s gaze was angry but distant, while Lord Murdach looked like a mad bear, with froth about his lips and hair barely braided back from his gargantuan frame. “Ah, daughter of Master Adwr, yes?” I curtsied and greeted as manners dictated. “You’re a big favorite of Master Prydwen, you and your whole family. Gods know your father’s holdings have nearly quadrupled these past three years, your sisters donned in velvet and pearls every day.”

Caddock snorted. “You see velvet and pearls on this one?”

“No…no, you have a point there, my friend, I don’t. Look up, girl.” Lord Murdach studied my roughspun cloak and shawls and cold eyes. “You don’t seem too taken with the man.”

I curtsied again, my breath slight puffs in the air. “I find him generous with words and coin, yet miserly with motive.”

“Motive. Yes. Yes, girl, that is the crux. And the sage is useless, of course, fopping over himself to bring more good news of Cairbail’s future thanks to Golden Prydwen. I wonder if the King’s Stronghold would have another sage untainted by this…whoever he is…” Lord Murdach mumbled himself out the warehouse and into the street.

Caddock waited until the mumbling fell into the ebb and flow of street noise before speaking once more. “Have a care, Wynne. That sort of man’s not to be antagonized.”

I settled onto my favorite seat, the old barrel saved for apple cores and fruit skins. “I wasn’t rude to Lord Murdach.”

“I do not speak of Lord Murdach.”

“Why do you stare so? I care nothing for his intentions, I have been clear on the subject, I will not accept gifts from a man and lead him on as Mother instructs. That is rude, and selfish, and—”

“Wynne!” He shot my name like an arrow and silenced me. Caddock muzzled himself with his own hands, breathing heavily, the muscles of his neck tight as a growling guard hound…at last he sat next to me and unloosed his tongue. “A man like that does not hear ‘no.’ Only ‘you haven’t won me yet.’ I know his kind, Wynne. Men who insist on more than one wife wield an entirely different sort of greed. Your sisters may be cloth-eared, empty-headed ninnies, but they’re beautiful, and that’s a man who clearly likes his beautiful things.”

“Why do you think I dress as I do? To prove I’m not beautiful.”

Caddock smiled sadly. “You cannot hide real beauty, girl. I’m sorry.”

“But…but I don’t want to. I just…I already…” I pulled a handkerchief from my pocket to catch the tears before they blot my face and betray my feelings to outside eyes. But I had forgotten what was wrapped in the linen: my iron orpine fell softly into my lap.

Caddock, of course, snatched it from the air before it hit the sawdust on the floor. “You’ve already given your heart, haven’t you, Wynne?” I opened my mouth to beg him, to unleash words of mercy and hope secrecy, but he raised his hand to silence me. And, with his head close for secrets as when we shared our love of the river Galene, he laughed. “Good. Now I know your family hasn’t a hope of influencing you down the years.” Caddock whistled as he delicately traced the leaves. “Your boy has skill, impressive skill.”

Pleasure filled me, for Caddock’s compliments do not come easily. I knew my Morthwyl could amaze others! “The smithy’s son in Little Innean, Morthwyl.”

“That’s a fair walk north. What brought you two together?”

I had to laugh. “Galene. She led me to him, actually.”

“The goddess holds you highly, Wynne, make no mistake.” He placed the orpine back in my hand and folded my fingers down upon it. “This promises a fine future for you both, if you could…one moment.” Caddock ran out. How strange the warehouse felt in his absence! No longer a sanctuary, but a maze of shadows and sharp corners I could never navigate were Prydwen’s men to follow…Thank the gods Caddock returned before my fears could grow any darker. “Can you visit the boy today?” He moved with a skittish urgency, pulling charts and maps from a chest precariously balanced on rotting crates.

“I was just there, but yes, I think so. If we’re not to dine with him again. Heledd’s not complained, at least.”

“Good.” He unrolled a large map, nearly torn apart in three places, littered with notes and arrows and scrawls. Idana, our country, looked a child’s mess. “Then let us hope the river goddess’ watch is vigilant.” His finger followed the river north, past Cairbail, the King’s Stronghold, and into forests far from the northern towns. “I’ve a barge to leave before daybreak tomorrow. Get the smithy’s son and yourself ready to be on it.”

My heart felt as a falcon loosed from its hood. Was it possible? Could I really escape Hafren and all its scheming souls? But I paused. Morthwyl loved his family, all kind, gentle people who did depend on him. “How far north would it take us?”

“As far north as I pay them. Till Galene’s beginnings, if possible.” Caddock breathed deep. “He won’t let you marry your boy, nor will your family. And he wants you for something, Wynne. He doesn’t have his ‘men,’ whatever those creatures are, following your sisters. Just you.”

“Because I’ve yet to agree to the marriage.”

Caddock looked up with an expression I will never forget: the paleness of his skin beneath his hair, the slight tremble of his chin, the way his voice fell to a whisper.

Caddock was afraid. Very afraid.

“No, it’s more than that. I’ve heard your father boast of meeting Prydwen the same day the river saved you, of how Prydwen looks just like his son. I, too, met Prydwen years ago, when I was but five, and Heledd seven. Galene bid us hide and be silent for not one but three days. It was torture to lay among the rocks and briars, but in those days a strange merchant bearing a golden hound upon his chest and a caged wagon of slaves interrogated my town for what he called ‘friends of the goddess.’ It took threat of the King’s Company to drive him out. That’s no son, Wynne. That is the same Prydwen.”

Thanks so much for reading! We’re nearly at the end of my dialogue with Wynne. I’d love to hear your feedback on this moment, or on any of the other moments of Wynne’s childhood–a prequel, you could say, to her adventure in Beauty’s Price.

Read on, share on, and write on, my friends!

So many writing manuals intend to guide you in making the most out of spare time: you can be a

So many writing manuals intend to guide you in making the most out of spare time: you can be a

Snarls rumbled in the low branches. Swift, eager sniffs and snaps of jaws. “Y-you c-c-c—“ I needed to speak, but fear found new footing inside me and crushed my heart. I struggled against the hold of that guard, but he was so bloody strong I could not break free. Oh for a weapon that day! “You can’t!”

Snarls rumbled in the low branches. Swift, eager sniffs and snaps of jaws. “Y-you c-c-c—“ I needed to speak, but fear found new footing inside me and crushed my heart. I struggled against the hold of that guard, but he was so bloody strong I could not break free. Oh for a weapon that day! “You can’t!”

“Oh…” Mother spoke of [orpines] often, promising many potential suitors we would plant them in our garden to divine which of my sisters they would marry. The three times she actually did instruct Father to purchase orpine for planting, however, one set grew straight as corn, one grew sick, and one simply died. Not one flower grew to touch another, and therefore promise marriage. Now I sat with one resting upon my arm. Morthwyl released his, and it leaned forward to grace the petals’ tips in the most chaste of kisses.

“Oh…” Mother spoke of [orpines] often, promising many potential suitors we would plant them in our garden to divine which of my sisters they would marry. The three times she actually did instruct Father to purchase orpine for planting, however, one set grew straight as corn, one grew sick, and one simply died. Not one flower grew to touch another, and therefore promise marriage. Now I sat with one resting upon my arm. Morthwyl released his, and it leaned forward to grace the petals’ tips in the most chaste of kisses. “Can I play computer games today?” She calls after reading a few chapters from her latest library acquisition,

“Can I play computer games today?” She calls after reading a few chapters from her latest library acquisition,